by Walker Larson

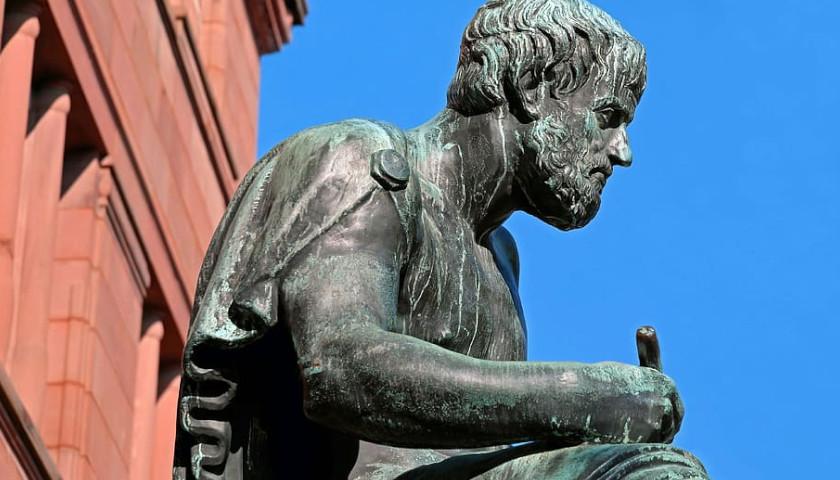

It is through wonder that men now begin and originally began to philosophize; wondering in the first place at obvious perplexities, and then by gradual progression raising questions about the greater matters too, e.g. about the changes of the moon and of the sun, about the stars and about the origin of the universe.

Wonder is the beginning of wisdom. And that sense of wonder begins when we encounter something beautiful, mysterious, and bigger than us—like the stars.

But what if you don’t believe in stars in the first place?

The poisonous influence of centuries of rationalist skepticism, relativism, and, most recently, critical theory have destroyed our ability to wonder at the world. Our intellectual milieu for the past century, at least, has been dominated by what Paul Ricoeur called a “hermeneutics of suspicion.” We doubt, we question, we are disillusioned and disenchanted. There is, in modern intellectual thought, a heavy fog of ennui stifling everything. And ennui is the antithesis of reverential wonder.

In the realm of literature and culture, for example, the critical theorists have done exactly what their name implies: criticized. The purpose of critical theory has been to critique everything, to call everything into question: our institutions—like family, religion, government—our language, even truth itself.

Since postmodernism has largely given up on the idea of truth, its followers have rested content to squabble over “practical” questions of the political dominion, continuing to subvert the structure of society in the process. From their point of view, what else is there to do?

Imagine, for a moment, two men in a forest at night. The first man looks up through the interweaving limbs of the trees and sees a sky bedecked with a brilliant smattering of stars. With childlike wisdom, he doesn’t question their reality. Of course they are real. There they are, smoldering with a white-hot intensity against an ebony blanket. They are an everlasting mystery, singing to him in an ancient language of things timeless. The language is obscure, the melody an unknown pitch, the words not of this world, not breathed in air, but he bends his ear to listen, patiently, patiently—he catches a snippet of the refrain of this song of the spheres. Something leaps to life within him.

Beside him, a second man sits slumped on a log, head in his hands. He stares in front of him, a strange dream churning in his unblinking eyes. Where the first man sees heavenly light streaming into the forest, the second sees the tree trunks as prison bars. He will not look up. He says the stars are just the peepholes of the prison guards. If he tries to stand, his vision reels, and his steps falter—he does not believe in up or down, so he is unable even to walk. He slumps back down. He hates the wood because he has convinced himself that it is a cage and that he is alone in it.

The first man begins to hum, trying to recall the unearthly sweetness of the melody he overheard. His humming grows louder. Then he is singing—a rich baritone sifting through the trees.

At this sound, the second man lifts his head a little. He pauses. Listens. But then he only shakes his head sadly and complains of police sirens. The first man tries to shake his companion out of his stupor. He pleads with him. He tries to teach him the song. But to no avail. There is no waking the sitting man from his unnatural inertness. In the end, the singer moves off in the direction of the coming dawn.

Critical theory and the hermeneutics of suspicion operate on the premise that most of the world runs by hidden power dynamics in which someone is always victimizing someone else. Intellectual work for critical theorists consists primarily in unmasking the hidden operations of oppression. For them, all that we call “culture” amounts to nothing more than an elaborate screen for the maintenance of various nexuses of power. Indeed, the fundamental basis of all human relationships and interactions is domination, à la Paul-Michel Foucault. They do not see power as a right or a good that some people or institutions should have for the benefit of all; in their rebellious bitterness, they shake their pens at the skies, holding that virtually any use of power is an abuse of power.

The modern intellectuals’ obsession with power results from their tragic disillusionment with reality. If reality is just a figment of one’s imagination, if it is unknowable, if we are all trapped inside our own historically situated perceptions and the phenomena of our isolated experiences, hallucinating a dream of “the real,” what is the point of intellectual work at all?

We have lingered long enough with the skeptics and their dour dreams. For centuries, we followed the route of questioning and disbelieving. What has been the result? The 20th century was perhaps the bloodiest and darkest epoch in human history. We have looked into the gaze of the postmodern man, and “his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming.”

Maybe it’s time to wake from the dream. Maybe it’s time to return to a spirit of credulity instead of incredulity. A spirit of enchantment instead of disenchantment. A spirit of wonder instead of despair. Suppose truth were knowable. What an invitation to adventure that would be. What a culture we might bring forth if we, as a people, remembered what we used to know.

So, let’s begin again. Let’s begin, as Aristotle did, with the stars.

– – –

Walker Larson teaches literature at a private academy in Wisconsin. When not in the classroom or spending time with family and friends, he blogs about literature and education on his Substack The Hazelnut.